In JustTrace Q1 2013 we added support for analyzing GC roots that are static fields. The implementation of this feature uses ICorProfilerInfo2::GetAppDomainStaticAddress, ICorProfilerInfo2::GetThreadStaticAddress and so on. Among all these methods, there is a very interesting one, namely ICorProfilerInfo2::GetRVAStaticAddress. In this post I am going to focus on a little known CLR feature that is closely related to this method.

What I find so interesting in ICorProfilerInfo2::GetRVAStaticAddress method is the RVA abbreviation. It stands for relative virtual address. Here is the definition from Microsoft PE and COFF Specification:

In an image file, the address of an item after it is loaded into memory, with the base address of the image file subtracted from it. The RVA of an item almost always differs from its position within the file on disk (file pointer).

Once we know what RVA is, we can make a few reasonable guesses about RVA static fields. Since RVA should be known at compile/link time, it is reasonable to guess that the static field should be a value type and should not contain any reference types. We can use the same argument so that any RVA field should be static since it does not make sense to have multiple instance fields occupying the same RVA.

Lets try find out whether our guesses are correct. Because VB.NET\C# can specify only application domain static and thread static fields we should look at Standard ECMA-335. We are interested in RVA static fields, so it makes sense to look at the field definition specification (II.16 Defining and referencing fields)

Field ::= .field FieldDecl

FieldDecl ::=

[ ‘[’ Int32 ‘]’ ] FieldAttr* Type Id [ ‘=’ FieldInit | at DataLabel ]

The interesting thing here is the at clause. This clause is used together with a DataLabel, so we have to find out what DataLabel is. Reading the document further we can see that II.16.3 Embedding data in a PE file paragraph starts with the following words:

There are several ways to declare a data field that is stored in a PE file. In all cases, the .data directive is used.

The good thing is that the document provides the following example code:

.data theInt = int32(123)

.data theBytes = int8 (3) [10]

After reading a little bit further we find the following text:

[…]In this case the data is laid out in the data area as usual and the static variable is assigned a particular RVA (i.e., offset from the start of the PE file) by using a data label with the field declaration (using the at syntax).

This mechanism, however, does not interact well with the CLI notion of an application domain (see Partition I). An application domain is intended to isolate two applications running in the same OS process from one another by guaranteeing that they have no shared data. Since the PE file is shared across the entire process, any data accessed via this mechanism is visible to all application domains in the process, thus violating the application domain isolation boundary.

Now, we know enough about RVA static fields so lets create a test scenario. I tried to keep it as simple as possible. I decided to create a console app that uses a class library, so I can replace the class library assembly with different implementation. Here is the source code for the console app:

using System;

namespace ConsoleApplication1

{

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

PrintStaticVar();

AppDomain app = AppDomain.CreateDomain("MyDomain");

app.DoCallBack(PrintStaticVar);

AppDomain.Unload(app);

}

unsafe static void PrintStaticVar()

{

fixed (int* p = &ClassLibrary1.Class1.MyInt)

{

IntPtr ptr = new IntPtr(p);

Console.WriteLine("app {0}, static {1:X}, addr {2:X}",

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.FriendlyName,

ClassLibrary1.Class1.MyInt,

ptr.ToInt64());

}

}

}

}

As you can see, it prints the value and the address of MyInt static variable and it does so for the two application domains. Here is the source code for the class library:

using System;

namespace ClassLibrary1

{

public class Class1

{

public static int MyInt = 0x11223344;

}

}

The output from running the console app is as follows:

app ConsoleApplication1.exe, static 11223344, addr AF3C74

app MyDomain, static 11223344, addr E23EAC

Press any key to continue . . .

As you can see, the app prints unique address for each application domain. Now, it is time to provide different implementation for ClassLibrary1. This time we should write it in ILAsm:

.assembly extern mscorlib

{

.publickeytoken = (B7 7A 5C 56 19 34 E0 89)

.ver 4:0:0:0

}

.assembly ClassLibrary1

{

.ver 1:0:0:0

}

.data MyInt_Data = int32(0x11223344)

.class public auto ansi ClassLibrary1.Class1

extends [mscorlib]System.Object

{

.field public static int32 MyInt at MyInt_Data

}

The last thing we have to do is to run the console app once again. Here is output:

app ConsoleApplication1.exe, static 11223344, addr 7A4000

app MyDomain, static 11223344, addr 7A4000

Press any key to continue . . .

As expected, this time the app prints the same address for both application domains. If you run the following command

dumpbin.exe /all ClassLibrary1.dll

and examine the output then you should see something similar

SECTION HEADER #2

.sdata name

4 virtual size

4000 virtual address (00404000 to 00404003)

200 size of raw data

600 file pointer to raw data (00000600 to 000007FF)

0 file pointer to relocation table

0 file pointer to line numbers

0 number of relocations

0 number of line numbers

C0000040 flags

Initialized Data

Read Write

RAW DATA #2

00404000: 44 33 22 11 D3".

Summary

2000 .sdata

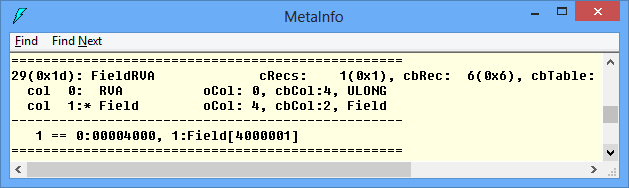

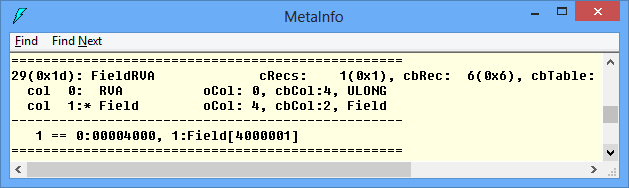

We can see that the ILAsm compiler emitted MyInt_Data value in the .sdata section. Cross checking with ILDasm only assures us that FieldRVA table contains the correct RVA.

Lets check our guess that RVA static fields should be value type only. It is easy to modify our code by adding the following lines appropriately:

.data MyString_Data = char*("test")

//...

.field public static string MyString at MyString_Data

If you try to run the console app again you will get System.TypeLoadException.

In closing, I think RVA static fields are little known CLR feature because they aren’t very useful. It is good know that the CLR has this feature but I guess its practical usage is limited.